Statistical Inference in Regression

February 3, 2026

The Highlights

Are our models useful?

- Global tests for model utility

- Tests on individual model terms

Confidence Intervals for Coefficients

Intervals for Model Predictions

- Confidence Intervals

- Prediction Intervals

Playing Along

Open your notebook from last time

As we discuss the different hypothesis test and interval analyses we’ll be encountering in the regression context, analyze the corresponding items for your models in that notebook

Global Test for Model Utility

\[y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \cdots + \beta_k x_k + \varepsilon\\ ~~~~\text{or}~~~~\\ \mathbb{E}\left[y\right] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \cdots + \beta_k x_k\]

Does our model contain any useful information about predicting/explaining our response variable at all?

Hypotheses:

\[\begin{array}{lcl} H_0 & : & \beta_1 = \beta_2 = \cdots = \beta_k = 0\\ H_a & : & \text{At least one } \beta_i \text{ is non-zero}\end{array}\]

| r.squared | adj.r.squared | sigma | statistic | p.value | df | logLik | AIC | BIC | deviance | df.residual | nobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7834185 | 0.7579384 | 6.253346 | 30.7462 | 2.3e-06 | 2 | -63.41591 | 134.8318 | 138.8148 | 664.7737 | 17 | 20 |

Result: Since our \(p\) value is less than \(0.05\) (it’s about \(2.3 \times 10^{-6}\)), we reject the null hypothesis and accept that at least one of the terms in our model has a non-zero coefficient.

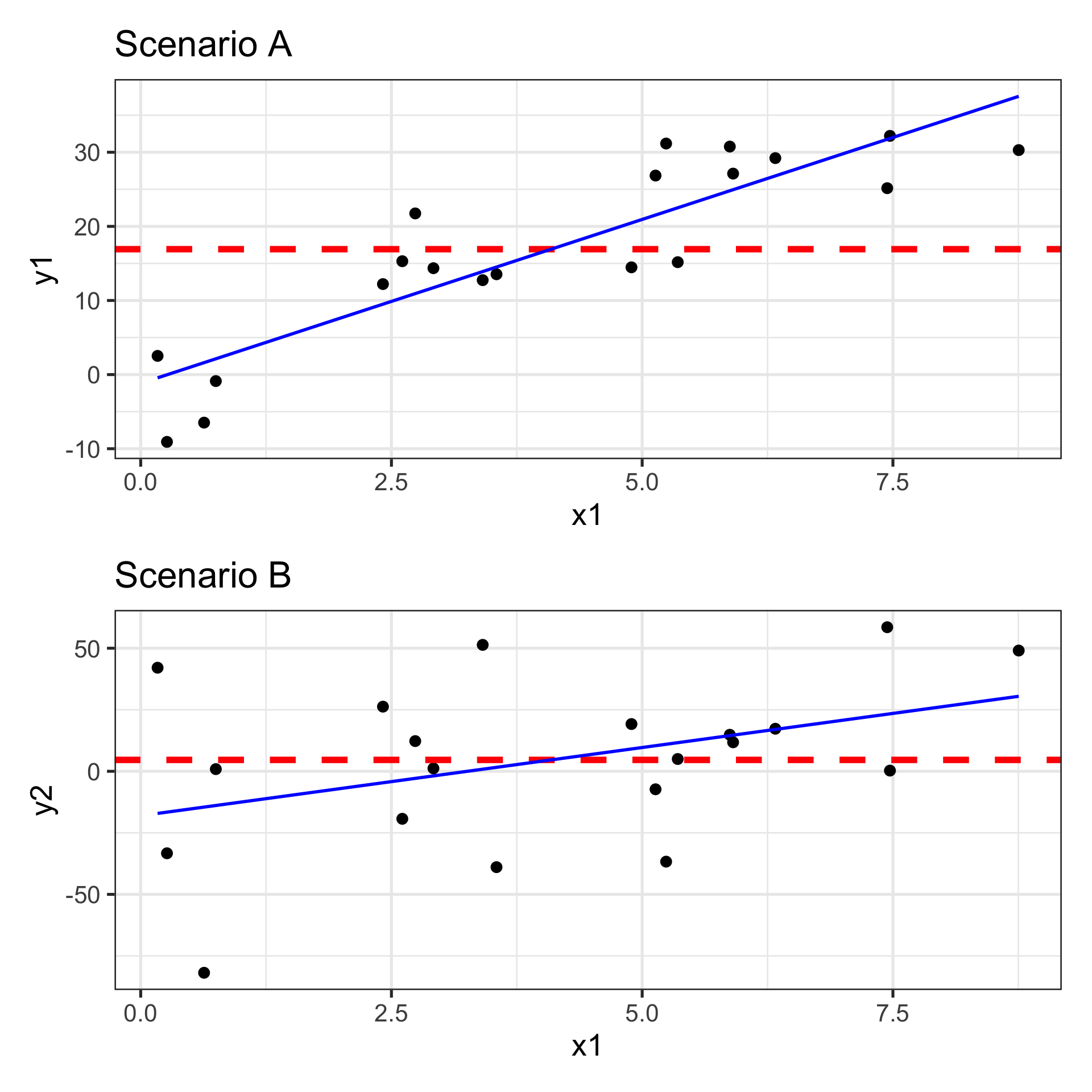

Global Test for Model Utility in Pictures

\[\begin{array}{lcl} H_0 & : & \beta_1 = \beta_2 = \cdots = \beta_k = 0\\ H_a & : & \text{At least one } \beta_i \text{ is non-zero}\end{array}\]

Are our sloped models better (more justifiable) models than the horizontal line?

Sloped models use predictor information

Horizontal models just predict average response, ignoring all observation-specific features

- They assume that having information about features of an observation gives no advantage in predicting/explaining its response

Additional Global Metrics from glance()

| r.squared | adj.r.squared | sigma | statistic | p.value | df | logLik | AIC | BIC | deviance | df.residual | nobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7834185 | 0.7579384 | 6.253346 | 30.7462 | 2.3e-06 | 2 | -63.41591 | 134.8318 | 138.8148 | 664.7737 | 17 | 20 |

The output from glance()ing at our fitted model object gives lots of additional information about overall model fit and quality.

- The adjusted R-squared value (

adj.r.squared) measures the proportion of variation in the response variable which is explained by the terms in our fitted model. - The adjusted R-squared value is a better measure than R-squared because adjusted R-squared penalizes the inclusion of additional model terms.

- The

sigmavalue is our residual standard error, which we’ll often call our “training error”. It is a measure of how far off we should expect our predictions to be, on average (but it is a biased measure). - We won’t generally consider the additional items in our course.

Tests on Individual Model Terms

\[y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \cdots + \beta_k x_k + \varepsilon\\ ~~~~\text{or}~~~~\\ \mathbb{E}\left[y\right] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \cdots + \beta_k x_k\]

Okay, so our model has some utility. Do we really need all of those terms?

Hypotheses:

\[\begin{array}{lcl} H_0 & : & \beta_i = 0\\ H_a & : & \beta_i \neq 0\end{array}\]

| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -1.9159203 | 3.6992261 | -0.5179246 | 0.6111856 |

| x1 | 4.4392216 | 0.5669213 | 7.8304022 | 0.0000005 |

| x2 | 0.1225861 | 0.4234080 | 0.2895224 | 0.7756830 |

Result: The x1 predictor is statistically significant but the x2 predictor is not. We should drop the x2 predictor from the model and re-fit it. (\(\bigstar\) We’ll only ever drop one predictor / model term at a time, using the highest p-value to indicate which.)

Confidence Intervals (Model Coefficients)

Reminder: An approximate 95% confidence interval is between two standard errors below and above our point estimate.

\[\left(\text{point estimate}\right) \pm 2\cdot\left(\text{standard error}\right)~~~\textbf{or}~~~\left(\text{point estimate}\right) \pm t^*_{\text{df}}\cdot\left(\text{standard error}\right)\]

Model Predictions

They’re all wrong!

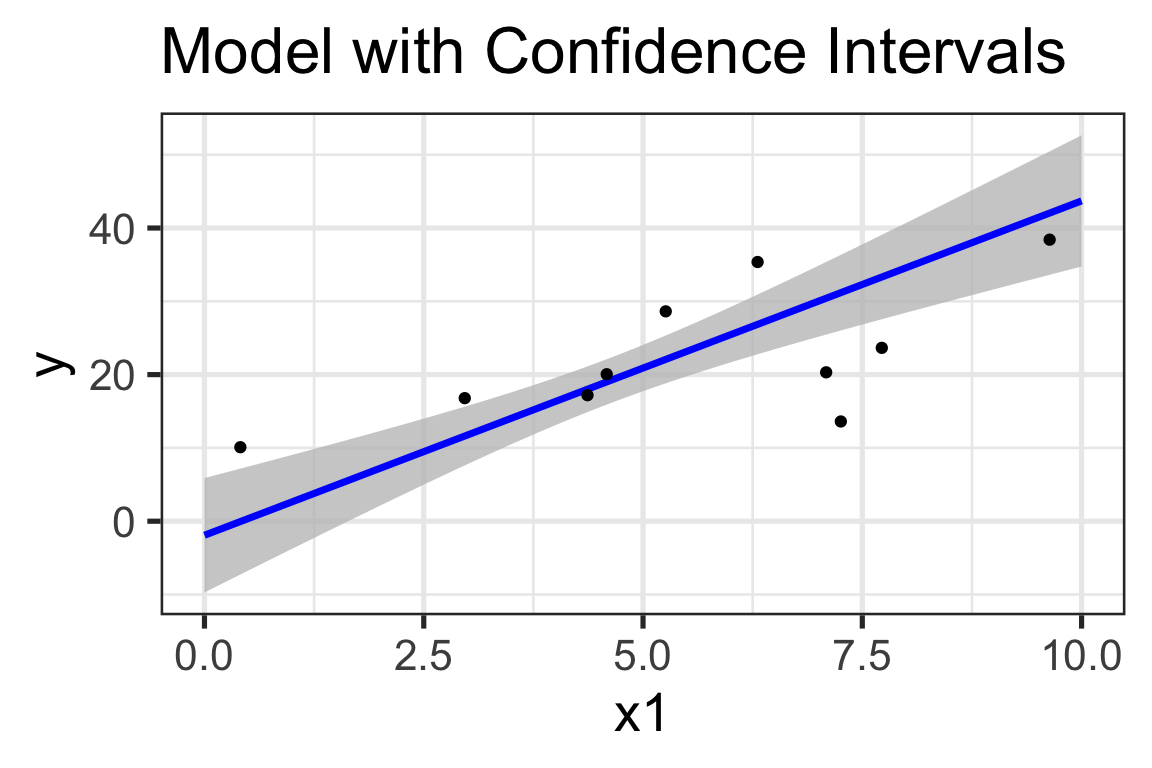

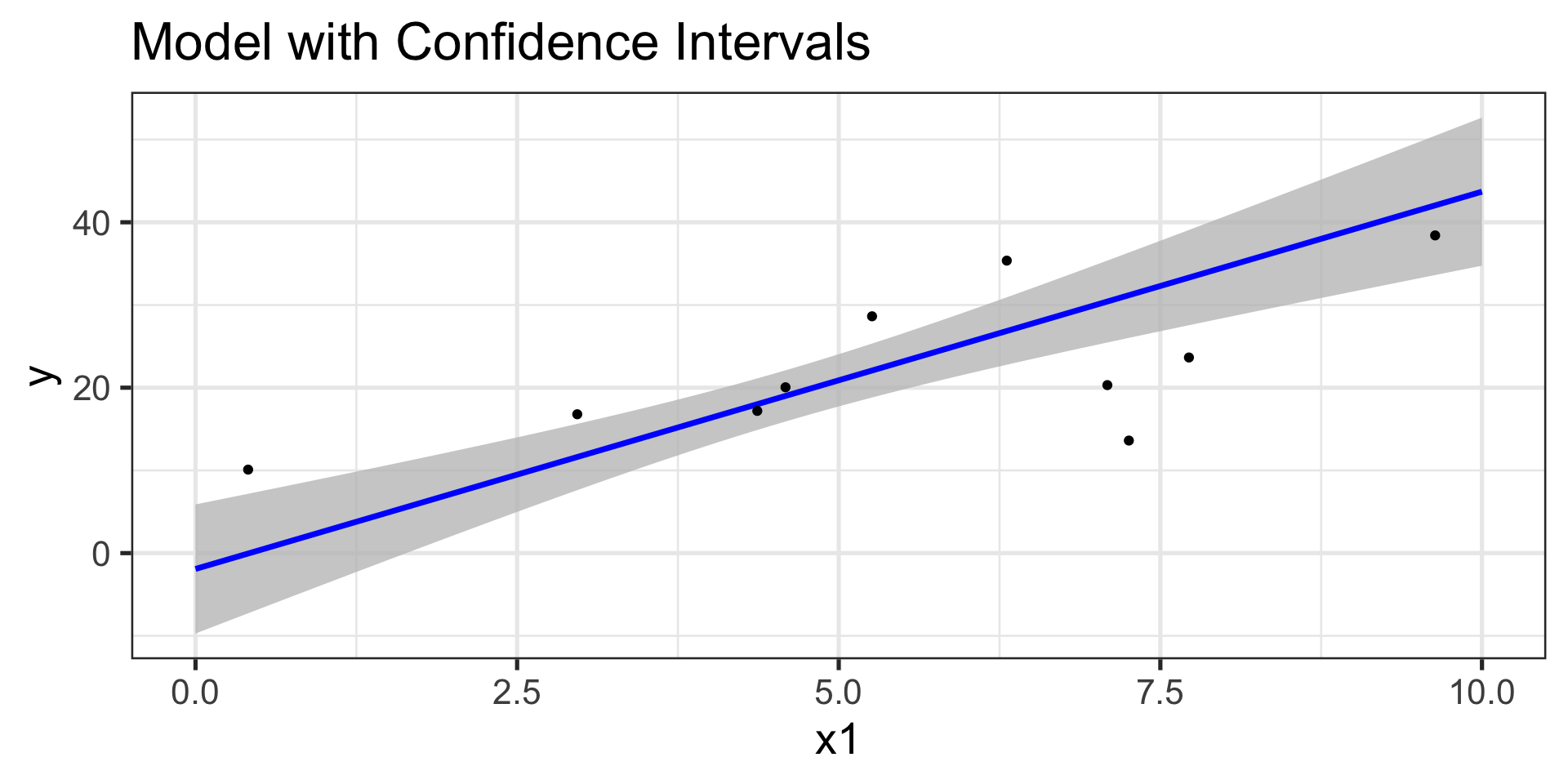

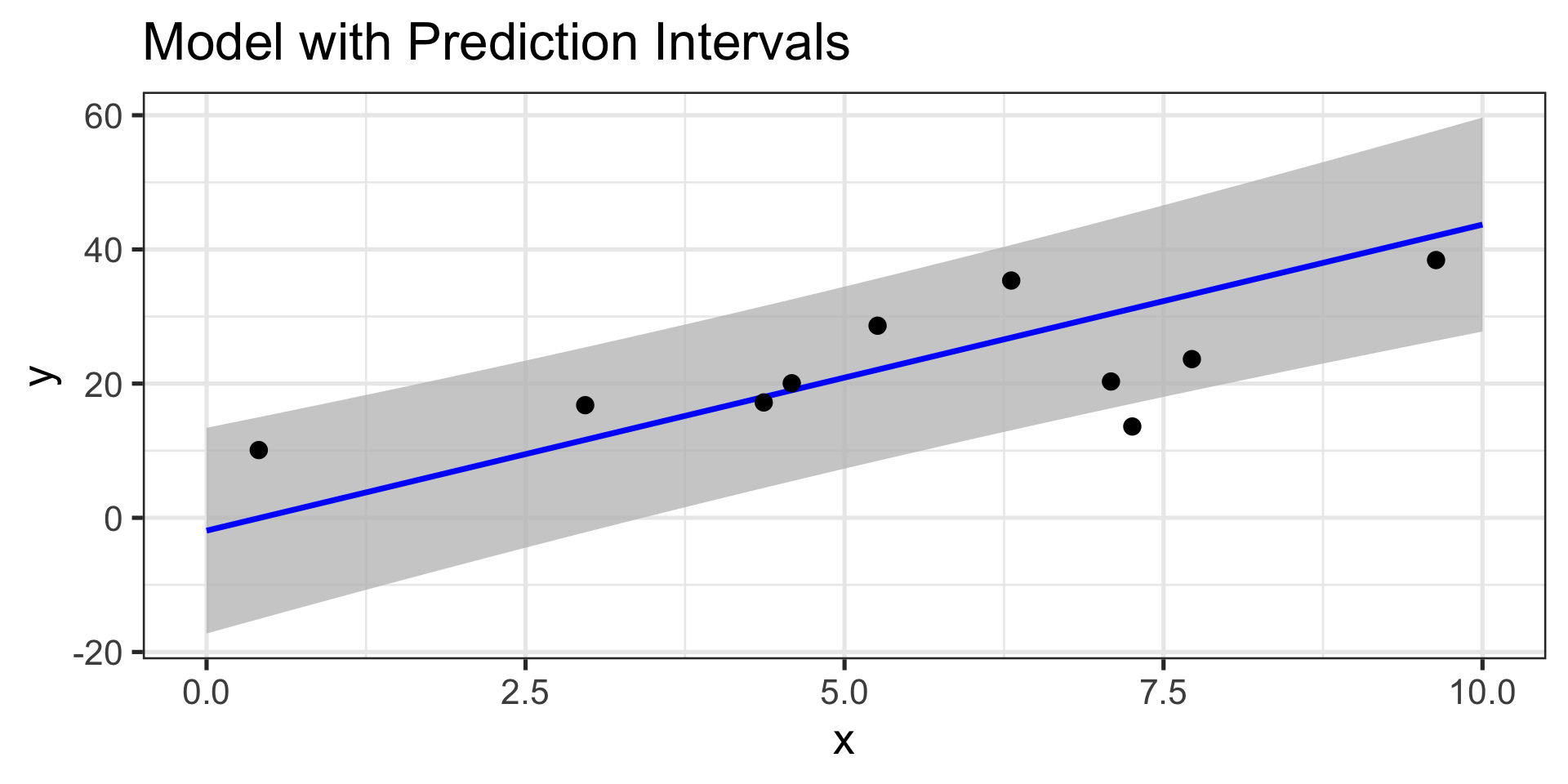

Confidence Intervals (Predictions)

The formula for confidence intervals on predictions is complex!

\[\displaystyle{\left(\tt{point~estimate}\right)\pm t^*_{\text{df}}\cdot \left(\tt{RMSE}\right)\left(\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} + \frac{(x_{new} - \bar{x})^2}{\sum{\left(x - \bar{x}\right)^2}}}\right)}\]

We’ll use R to construct these intervals for us.

Are these wrong too?

Confidence Intervals (Predictions)

The formula for confidence intervals on predictions is complex!

\[\displaystyle{\left(\tt{point~estimate}\right)\pm t^*_{\text{df}}\cdot \left(\tt{RMSE}\right)\left(\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} + \frac{(x_{new} - \bar{x})^2}{\sum{\left(x - \bar{x}\right)^2}}}\right)}\]

We’ll use R to construct these intervals for us.

Are these wrong too? No – confidence intervals bound the average response over all observations having given input features.

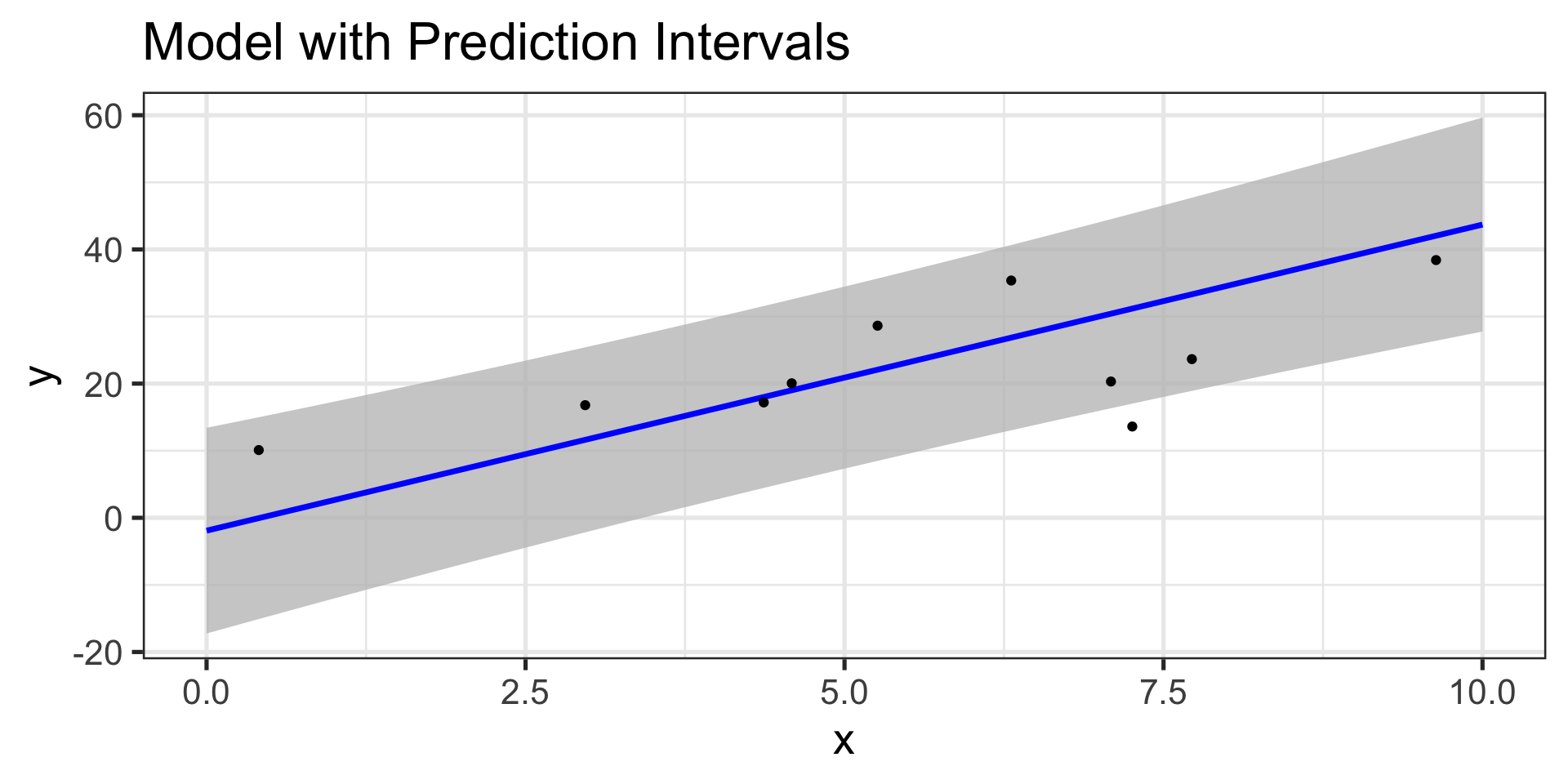

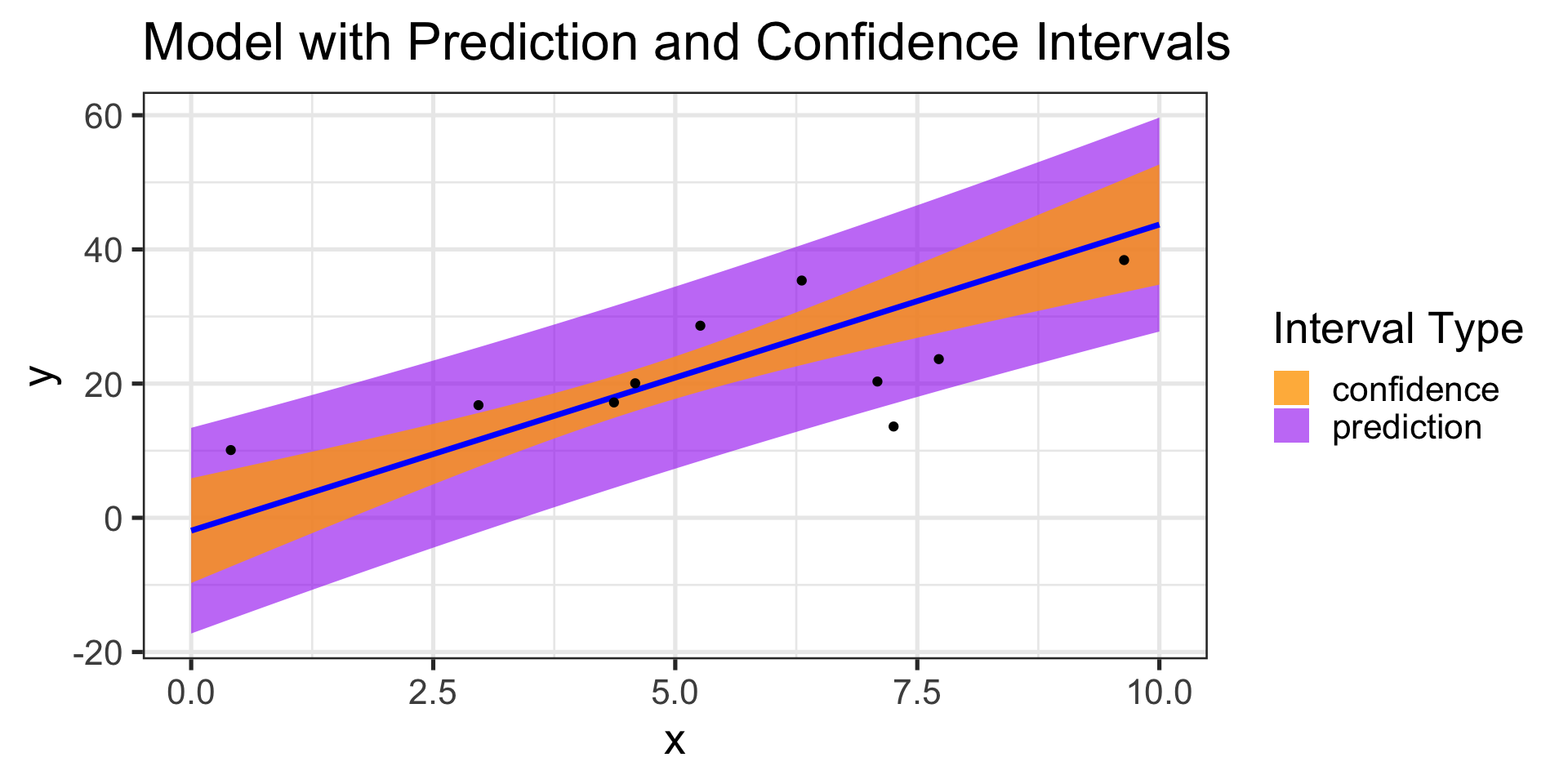

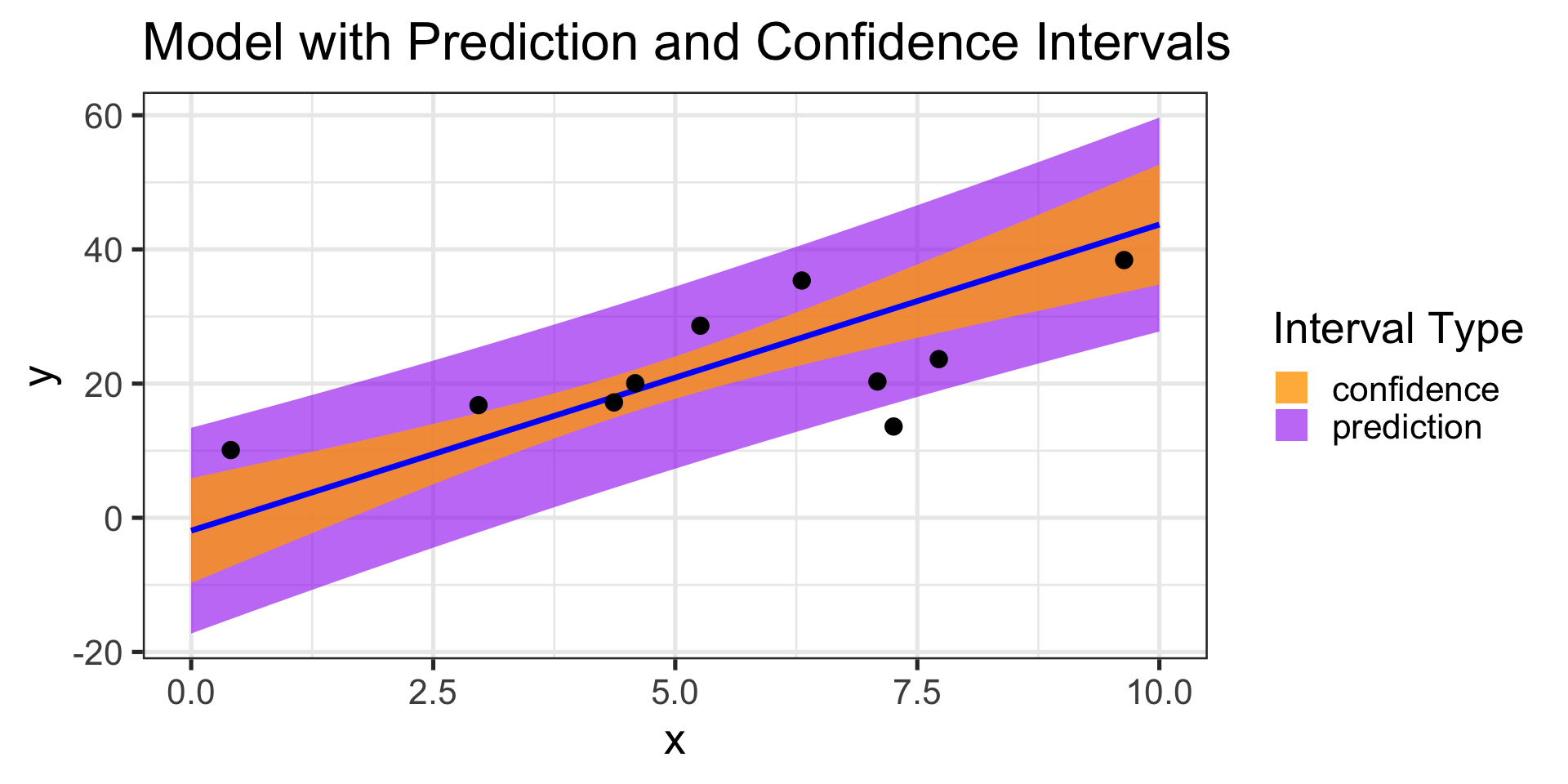

Prediction Intervals

So, can we build intervals which contain predictions on the level of an individual observation?

Sure – but there’s added uncertainty in making those types of predictions

Confidence and Prediction Intervals for Model Predictions

Summary

Below are the most common applications of statistical inference in regression modeling.

Hypothesis Tests

- Does our model have any utility at all?

- Are all of the included predictor terms useful?

Confidence Intervals

What is the plausible range for each parameter/coefficient?

- How do we interpret those ranges?

Can we make reliable predictions?

- Confidence Intervals for average response

- Prediction Intervals for individual response

We’ll be utilizing all of these ideas throughout our course.

We’ll leverage R functionality to obtain intervals or to calculate test statistics and \(p\)-values though, since it is much faster than doing any of this by hand.

Next Time…

Hypothesizing, Constructing, Assessing, and Interpreting Simple Linear Regression Models