Higher-Order Terms: Curvi-Linear Regression

October 22, 2024

Motivation

We’ll switch data sets for today.

This Boston housing dataset is quite famous (and problematic), and includes features on each neighborhood and the corresponding median home value in that neighborhood. You can see a data dictionary here. The data set has many interesting features and even allows us some ability to explore structural racism in property valuation in 1970s Boston.

| crim | zn | indus | chas | nox | rm | age | dis | rad | tax | ptratio | b | lstat | medv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00632 | 18 | 2.31 | 0 | 0.538 | 6.575 | 65.2 | 4.0900 | 1 | 296 | 15.3 | 396.90 | 4.98 | 24.0 |

| 0.02731 | 0 | 7.07 | 0 | 0.469 | 6.421 | 78.9 | 4.9671 | 2 | 242 | 17.8 | 396.90 | 9.14 | 21.6 |

| 0.02729 | 0 | 7.07 | 0 | 0.469 | 7.185 | 61.1 | 4.9671 | 2 | 242 | 17.8 | 392.83 | 4.03 | 34.7 |

| 0.03237 | 0 | 2.18 | 0 | 0.458 | 6.998 | 45.8 | 6.0622 | 3 | 222 | 18.7 | 394.63 | 2.94 | 33.4 |

| 0.06905 | 0 | 2.18 | 0 | 0.458 | 7.147 | 54.2 | 6.0622 | 3 | 222 | 18.7 | 396.90 | 5.33 | 36.2 |

| 0.02985 | 0 | 2.18 | 0 | 0.458 | 6.430 | 58.7 | 6.0622 | 3 | 222 | 18.7 | 394.12 | 5.21 | 28.7 |

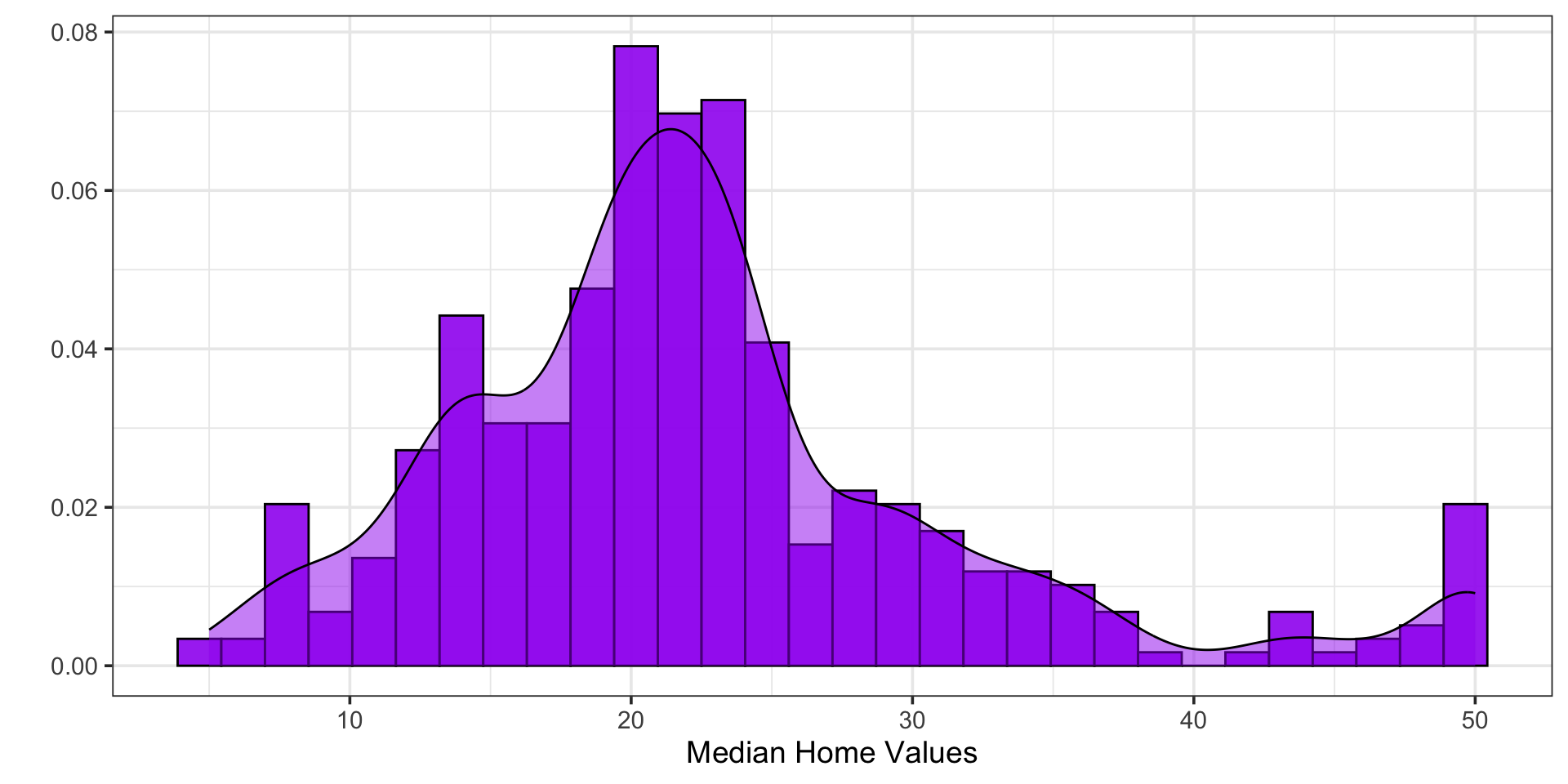

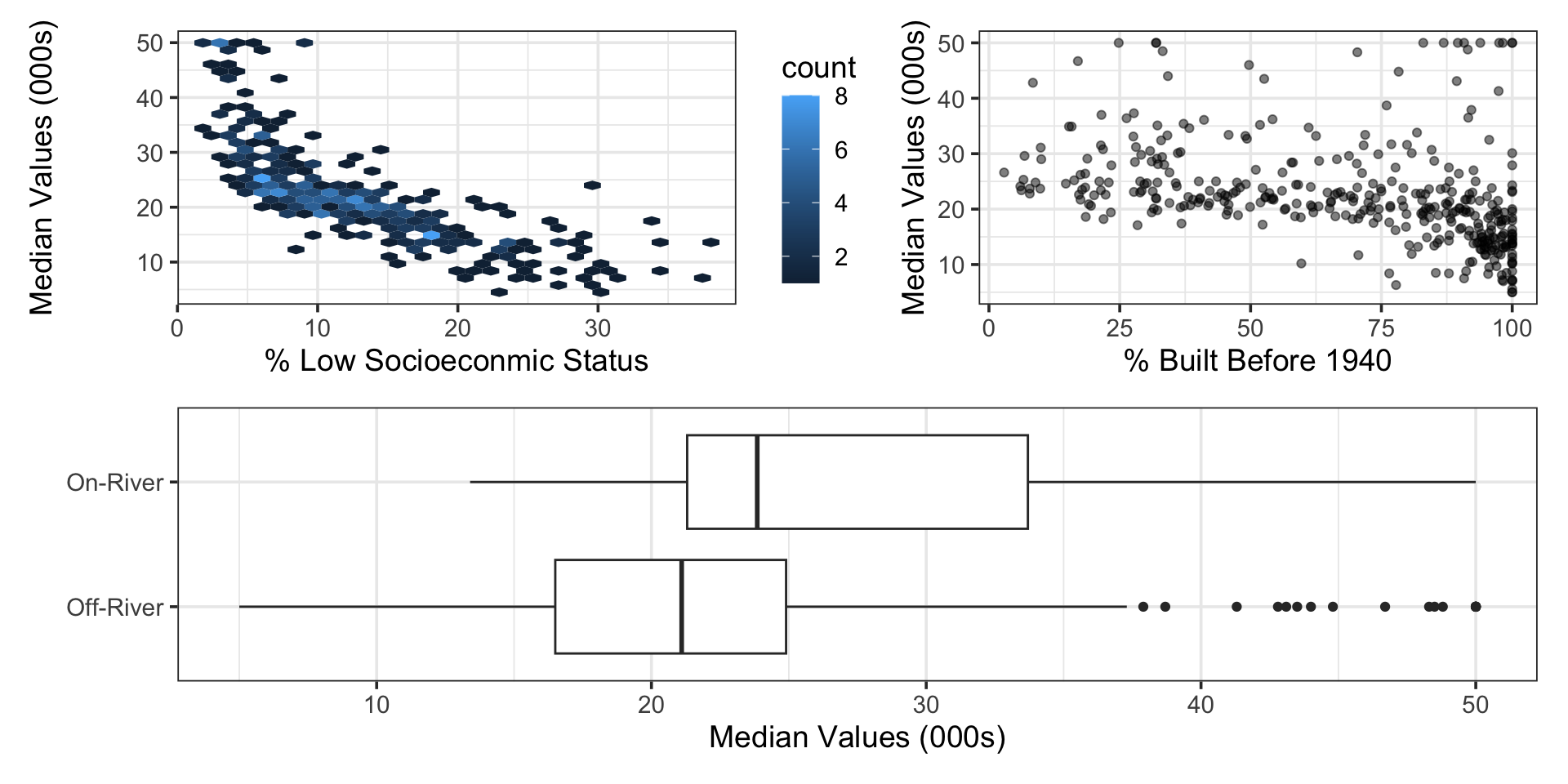

Motivation: Median Home Values

Motivation: Predictors Associated with Median Home Values

Motivation

Motivation

Motivation

Highlights

- Examples of higher-order terms in models

- What the inclusion of higher-order terms assumes about the relationship between the response and the corresponding predictor(s)

- Main effects terms versus mixed effects terms

- How to include polynomial terms in a recipe with

step_poly() - Term-based assessments of models with polynomial terms

- Interpreting models that include polynomial terms

Playing Along

You know by now that following along and writing/executing code during our in-class discussions is valuable.

For this notebook, either…

- follow along with the Boston Housing data as we go (start a new notebook)

- continue adding on to the notebook containing your models for rental prices

The choice is yours

Curvi-Linear Regression

We can use higher-order terms to introduce curvature to our models

Consider the following fourth-order model

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] = \beta_0 +~ &\beta_1\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + \beta_2\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_3\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) + \beta_4\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\right) + \beta_5\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) +\\ &~\beta_6\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}\right) + \beta_7\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_8\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}^2\right) +\\ &~\beta_9\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) + \beta_{10}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{11}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) +\\ &\beta_{12}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{13}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

Curvi-Linear Regression

The main effects terms are in blue

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] = \beta_0 +~ &\color{blue}{\beta_1\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + \beta_2\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_3\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) + \beta_4\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\right) + \beta_5\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right)} +\\ &~\beta_6\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}\right) + \beta_7\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_8\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}^2\right) +\\ &~\beta_9\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) + \beta_{10}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{11}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) +\\ &\beta_{12}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{13}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

Curvi-Linear Regression

The main effects terms are in blue

and the mixed effects terms are in purple

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] = \beta_0 +~ &\color{blue}{\beta_1\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + \beta_2\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_3\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) + \beta_4\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\right) + \beta_5\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right)} +\\ &~\color{purple}{\beta_6\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}\right) + \beta_7\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_8\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{age}^2\right) +}\\ &~\color{purple}{\beta_9\cdot\left(\text{chas}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) + \beta_{10}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{11}\cdot\left(\text{age}\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right) +}\\ &\color{purple}{\beta_{12}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_{13}\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\cdot\text{lstat}^2\right)} \end{align}\]

Curvi-Linear Regression

We’ll focus just on the main effects model today and wait to handle mixed effects (interactions) until next time

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] = \beta_0 +~ &\beta_1\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + \beta_2\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + \beta_3\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) + \beta_4\cdot\left(\text{age}^2\right) + \beta_5\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

Model Setup:

mlr_me_spec <- linear_reg() %>%

set_engine("lm")

mlr_me_rec <- recipe(medv ~ age + lstat + chas, data = boston_train) %>%

step_poly(age, degree = 2, options = list(raw = TRUE)) %>%

step_poly(lstat, degree = 2, options = list(raw = TRUE))

mlr_me_wf <- workflow() %>%

add_model(mlr_me_spec) %>%

add_recipe(mlr_me_rec)Curvi-Linear Regression

\(\bigstar\) Let’s try it! \(\bigstar\)

If you’re playing along with the Air BnB data…

- choose at least one of the available numeric predictors to include in polynomial terms

- create an instance of a linear regression model specification

- create a recipe and append

step_poly()to it in order to create the higher-order terms - package your model specification and recipe together into a workflow

Fit and Assess Model

Global Model Utility:

| r.squared | adj.r.squared | sigma | statistic | p.value | df | logLik | AIC | BIC | deviance | df.residual | nobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.703557 | 0.6995832 | 5.055401 | 177.0504 | 0 | 5 | -1148.907 | 2311.814 | 2339.377 | 9532.791 | 373 | 379 |

Individual Term-Based Assessments:

| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 39.8979924 | 1.3882165 | 28.7404684 | 0.0000000 |

| chas | 4.9606104 | 1.0056444 | 4.9327680 | 0.0000012 |

| age_poly_1 | 0.0975669 | 0.0506654 | 1.9257113 | 0.0549003 |

| age_poly_2 | -0.0002641 | 0.0004208 | -0.6277625 | 0.5305437 |

| lstat_poly_1 | -2.6383538 | 0.1457957 | -18.0962367 | 0.0000000 |

| lstat_poly_2 | 0.0482353 | 0.0041368 | 11.6600251 | 0.0000000 |

Drop the Curvi-linear Term for age

Re-Fit the Model to Training Data:

Assess Updated Model

Global Model Utility:

| r.squared | adj.r.squared | sigma | statistic | p.value | df | logLik | AIC | BIC | deviance | df.residual | nobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7032438 | 0.7000699 | 5.051304 | 221.5734 | 0 | 4 | -1149.107 | 2310.214 | 2333.839 | 9542.862 | 374 | 379 |

Individual Term-Based Assessments:

| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 40.5405112 | 0.9370994 | 43.261697 | 0.0000000 |

| age | 0.0666784 | 0.0120705 | 5.524075 | 0.0000001 |

| chas | 4.9657731 | 1.0047958 | 4.942072 | 0.0000012 |

| lstat_poly_1 | -2.6277451 | 0.1446957 | -18.160497 | 0.0000000 |

| lstat_poly_2 | 0.0477036 | 0.0040459 | 11.790647 | 0.0000000 |

A Note on Higher-Order Terms and Significance

If a higher-order term in a model is statistically significant, then all lower-order components of that term must be kept in the model

For example, if a term for age \(\cdot\) lstat \(^2\) is included in a model, then each of the following terms must be kept regardless of statistical significance

agelstatage\(\cdot\)lstatlstat\(^2\)

Fitting, Assessing, and Updating the Model (🔁)

\(\bigstar\) Let’s try it! \(\bigstar\)

Again, if you are playing along with your Air BnB data…

- fit your model workflow to your training data

- conduct both global and term-based model assessments

- reduce, refit, and reassess your model as needed

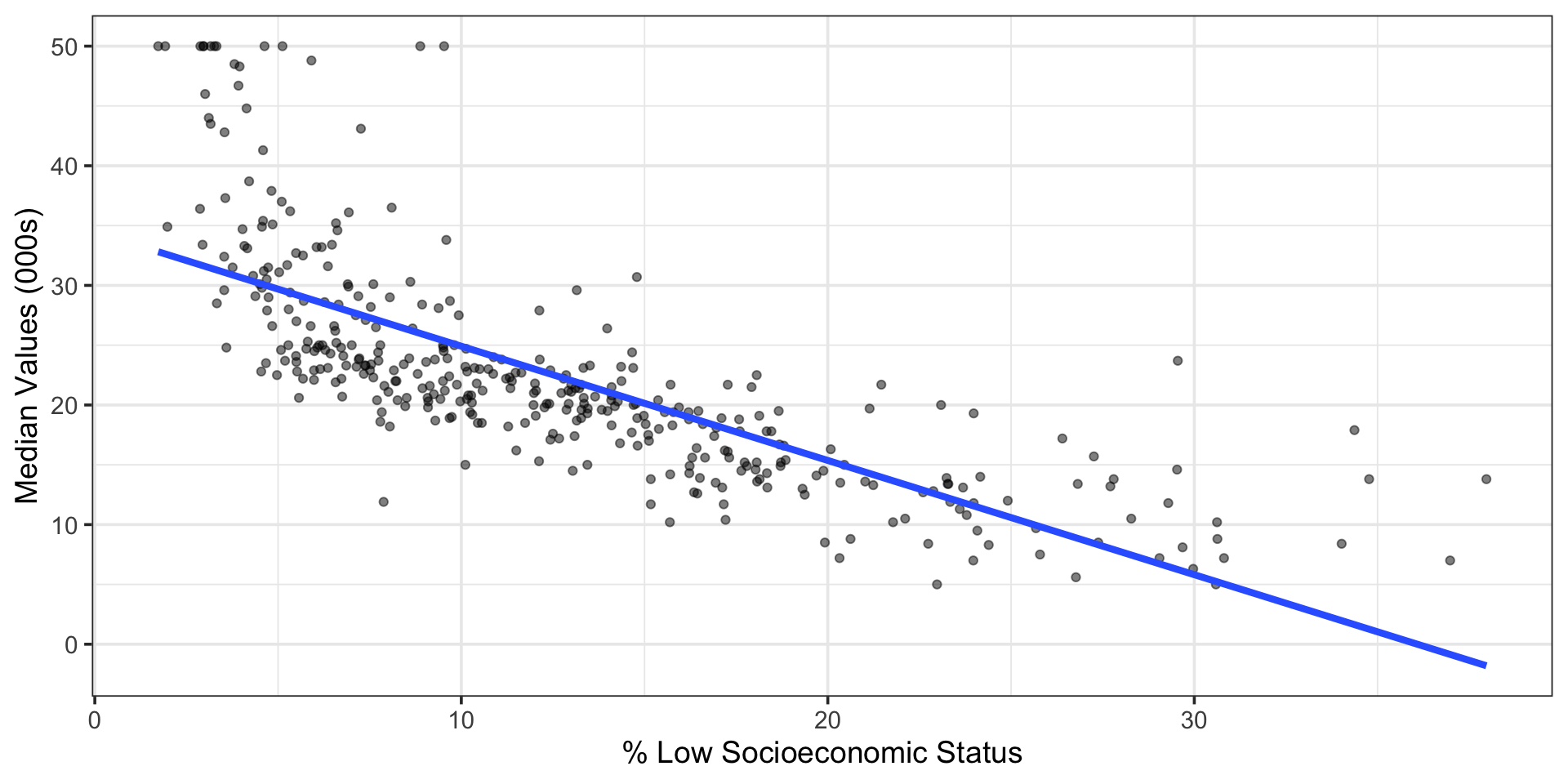

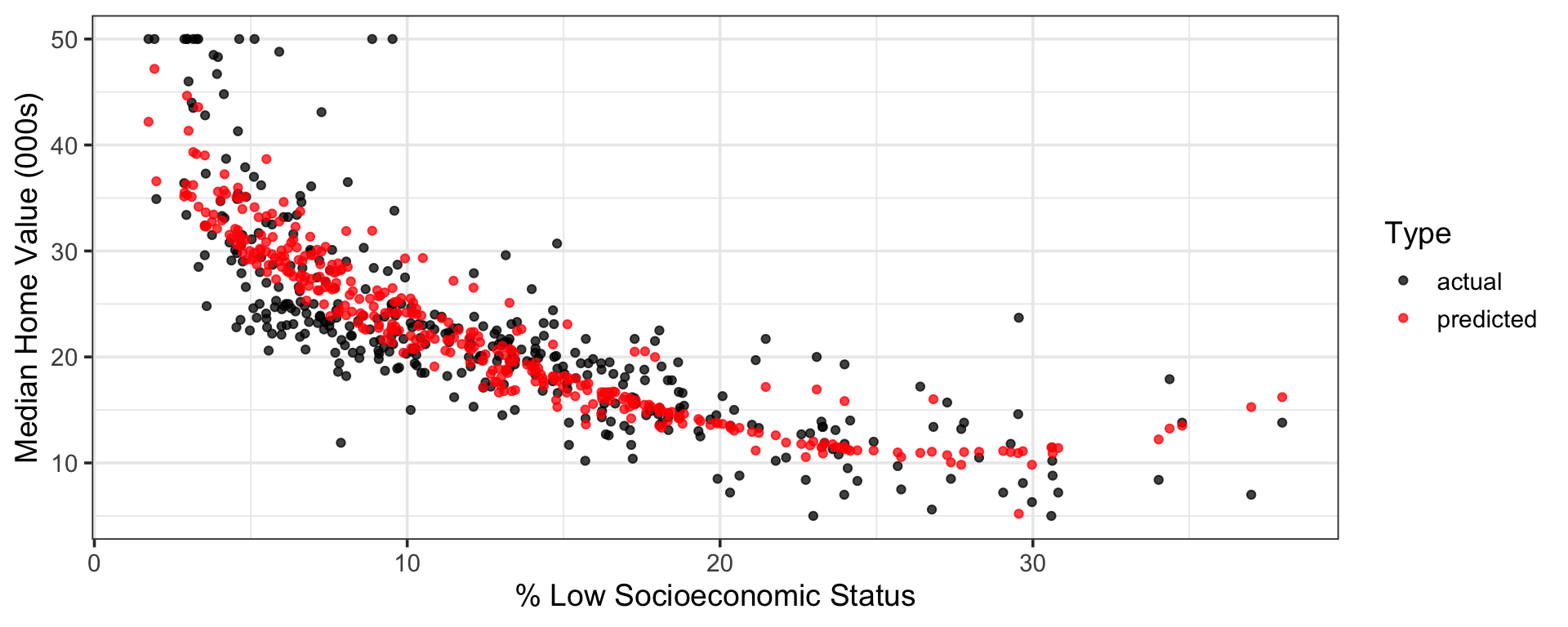

Visualizing Model Predictions [Training Data]

Code

point_colors <- c("actual" = "black", "predicted" = "red")

mlr_me_fit %>%

augment(boston_train) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(x = lstat, y = medv, color = actual),

alpha = 0.75) +

geom_point(aes(x = lstat, y = .pred, color = predicted),

alpha = 0.75) +

scale_color_manual(values = point_colors) +

labs(x = "% Low Socioeconomic Status",

y = "Median Home Value (000s)",

color = "Type")

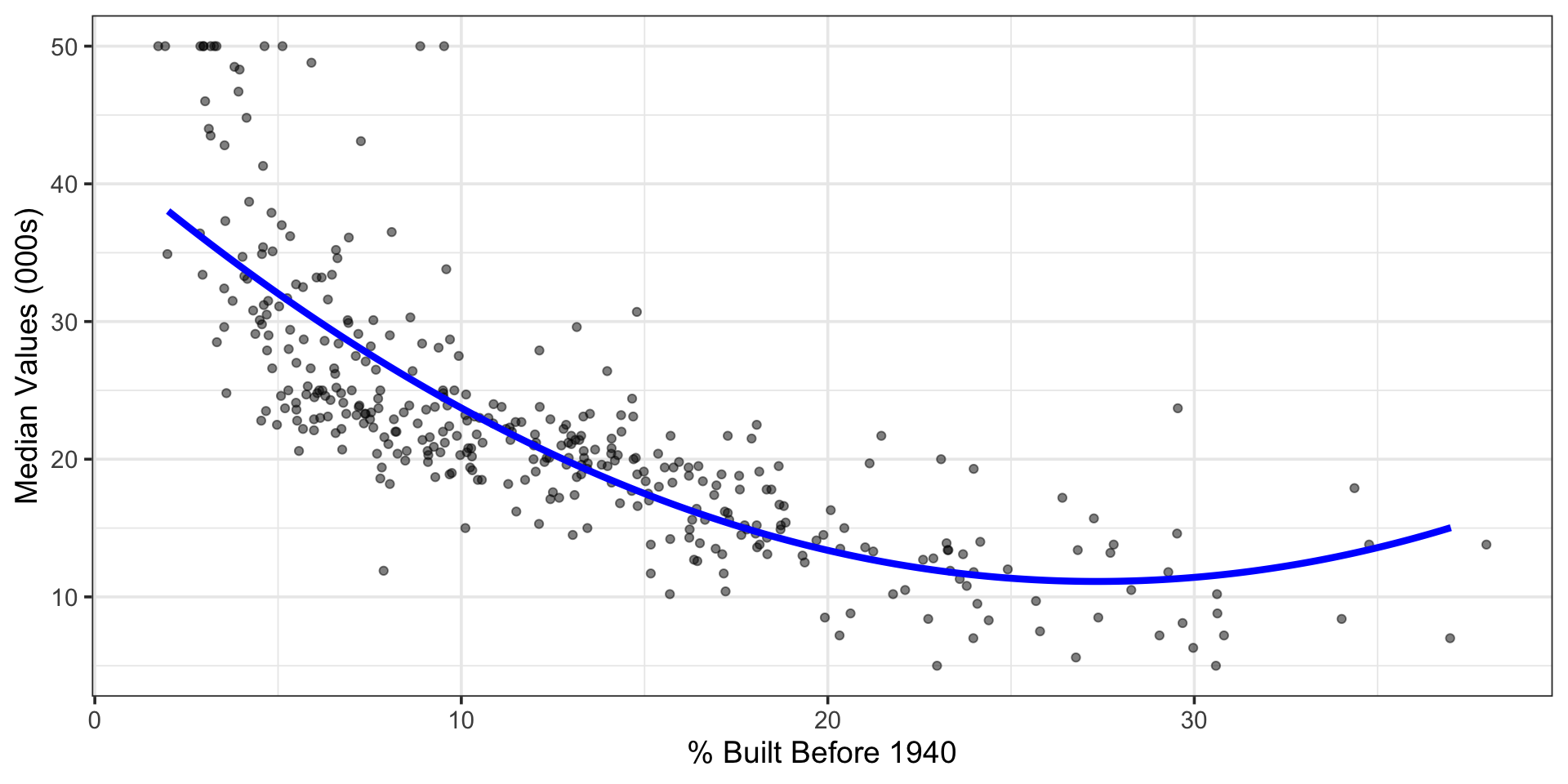

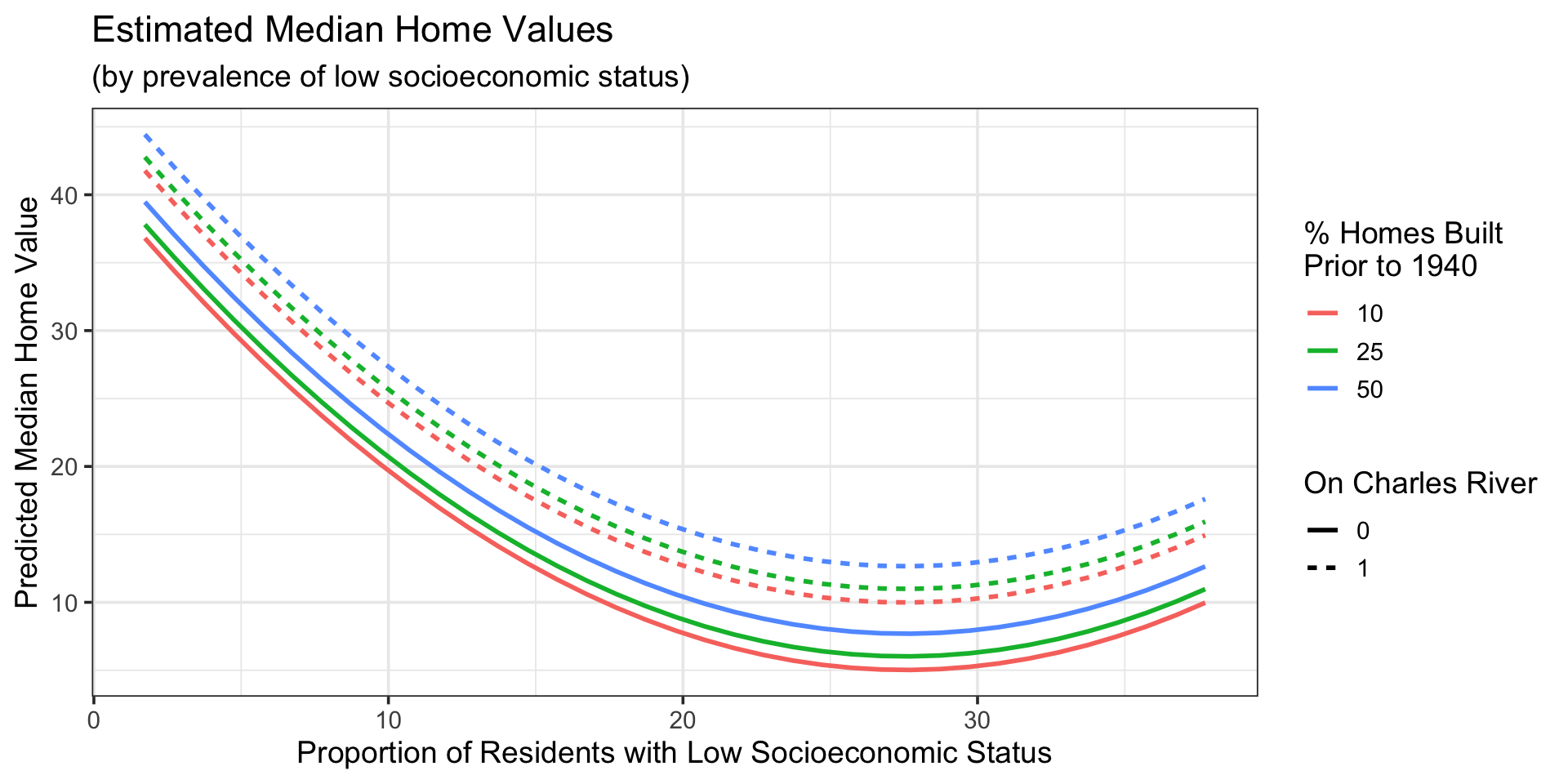

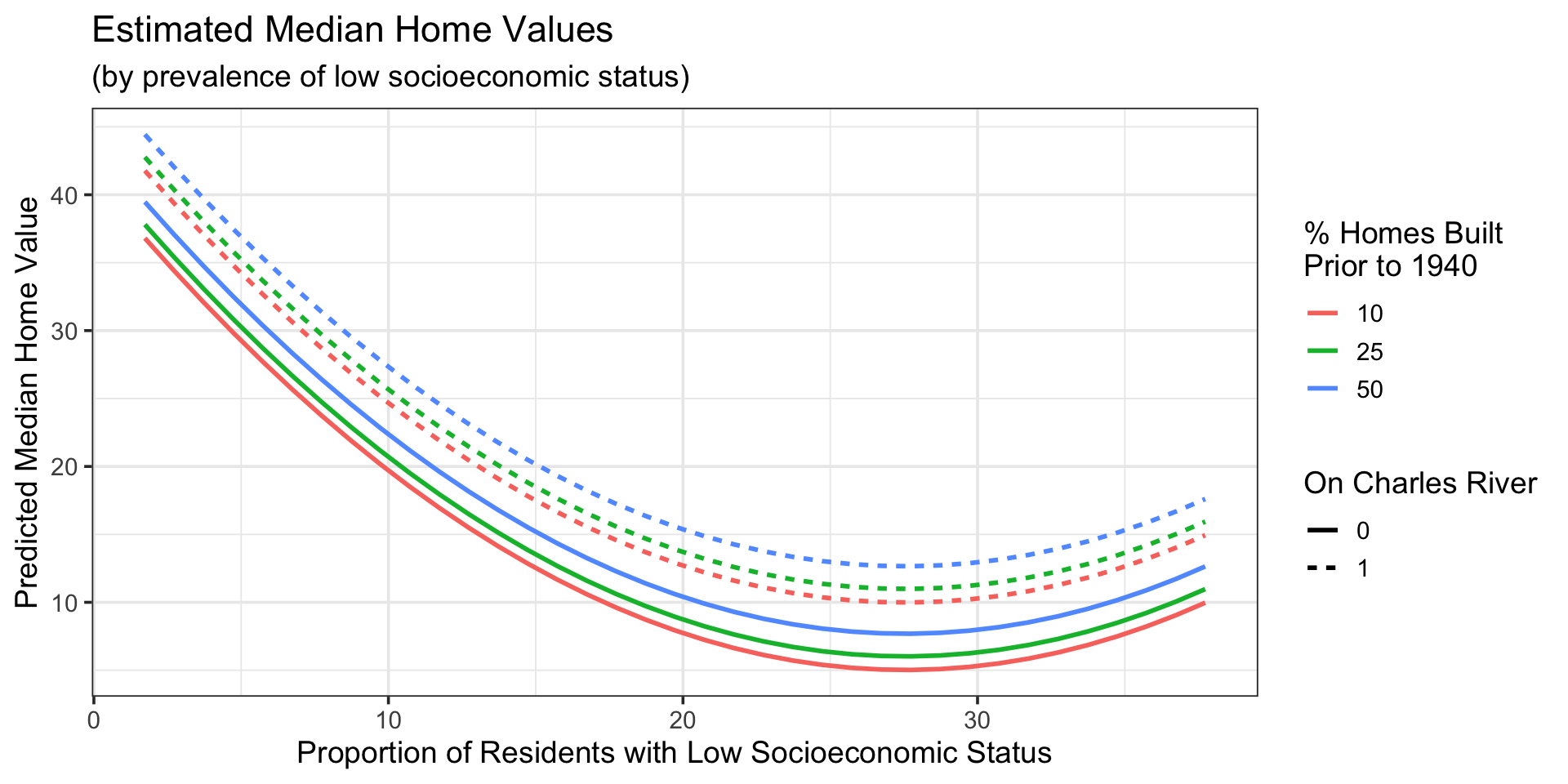

Model At Various Age Thresholds

Code

new_data <- crossing(age = c(10, 25, 50),

chas = c(0, 1),

lstat = seq(min(boston_train$lstat, na.rm = TRUE),

max(boston_train$lstat, na.rm = TRUE),

length.out = 250))

mlr_me_fit %>%

augment(new_data) %>%

ggplot() +

geom_line(aes(x = lstat,

y = .pred,

color = as.factor(age),

linetype = as.factor(chas)),

lwd = 1) +

labs(x = "Proportion of Residents with Low Socioeconomic Status",

y = "Predicted Median Home Value",

title = "Estimated Median Home Values",

subtitle = "(by prevalence of low socioeconomic status)",

color = "% Homes Built \nPrior to 1940",

linetype = "On Charles River")

- The model consists of curved surfaces

- One surface for when the neighborhood is on the Charles River, and another for neighborhoods off of it

- The cross-sections for each surface at different

agethresholds are parallel

Visualizing Model Predictions

\(\bigstar\) Let’s try it! \(\bigstar\)

For those still following along with the Air BnB data…

- plot your model’s fitted values along with the observed rental prices for your training data

- plot of your model’s predictions in relation to a predictor that has a higher-order term in your model – vary the values of the other significant predictors across different thresholds to visualize their effect, as in the previous slide

Interpreting the Model

Our Model:

| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 40.5405112 | 0.9370994 | 43.261697 | 0.0000000 |

| age | 0.0666784 | 0.0120705 | 5.524075 | 0.0000001 |

| chas | 4.9657731 | 1.0047958 | 4.942072 | 0.0000012 |

| lstat_poly_1 | -2.6277451 | 0.1446957 | -18.160497 | 0.0000000 |

| lstat_poly_2 | 0.0477036 | 0.0040459 | 11.790647 | 0.0000000 |

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] \approx 40.541 +~ &0.067\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + 4.966\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) - 2.628\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + 0.048\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

Interpreting the Model

Our Model:

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] \approx 40.541 +~ &0.067\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + 4.966\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) - 2.628\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + 0.048\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

- (Intercept) The expected median home value for a neighborhood with 0% of residents being of low socioeconomic status, 0% of homes built before 1940, and being away from the Charles River is about $40,541

- (age) Holding location relative to the Charles River and percentage of residents with low socioeconomic status constant, a one percentage-point increase in the proportion of homes built prior to 1940 is associated with an expected increase of about $67 in median home value

- (chas) Holding percentage of residents with low socioeconomic status and percentage of homes built before 1940 constant, a neighborhood on the Charles River is expected to have higher median home values by about $4,966

Interpreting the Model

Our Model:

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] \approx 40.541 +~ &0.067\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + 4.966\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) - 2.628\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + 0.048\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

- The association between

lstatand median home values is not constant! - The expected change in median home values due to a change in the percentage of residents with low socioeconomic status depends on the “current” percentage.

(lstat) Holding the location of a neighborhood relative to the Charles River and the percentage of homes built before 1940, a one percentage-point increase in the percentage of residents of low socioeconomic status is expected to be associated with a change in median home values of about

\[-2.628 + 2\cdot\left(0.048\right)\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right)~~~~~~~~\left(\text{times 1000 to convert to thousands}\right)\]

Interpreting the Model

Our Model:

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\text{medv}\right] \approx 40.541 +~ &0.067\cdot\left(\text{age}\right) + 4.966\cdot\left(\text{chas}\right) - 2.628\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right) + 0.048\cdot\left(\text{lstat}^2\right) \end{align}\]

(lstat) Holding the location of a neighborhood relative to the Charles River and the percentage of homes built before 1940, a one percentage-point increase in the percentage of residents of low socioeconomic status is expected to be associated with a change in median home values of about

\[-2.628 + 2\left(0.048\right)\cdot\left(\text{lstat}\right)~~~~~~~~\left(\text{times 1000 to convert to thousands}\right)\]

For Example: If the current percentage of residents of low socioeconomic status is 10%, then holding location relative to the Charles River and the percentage of homes build before 1940 constant, an increase to 11% of residents with low socioeconomic status is expected to be associated with a change in median home values by about

\[-2.628 + 2\left(0.048\right)\cdot\left(10\right) = -1.668\]

That is, a drop of about $1,668

Similarly, if the current percentage was 33%, then we would expect an increase of about $540 in a similar neighborhood but where the percentage of residents of low socioeconomic status is 34%

General Interpretation with a Squared Predictor

Consider a model of the form:

\[\mathbb{E}\left[y\right] = \beta_0 + \beta_1\cdot x + \beta_2\cdot x^2 + \cdots\]

where the only two terms involving the predictor \(x\) are the ones shown.

Interpretation of a Unit Increase in \(x\): Holding all other predictors constant, a unit increase in \(x\) is associated with an expected change in the response by about \(\beta_1 + 2\cdot\beta_2\cdot x\).

A Bit of Calculus: Those of you with a Calculus background will recognize this as the partial derivative of the model with respect to \(x\).

Taking the partial derivative is how you examine the effect of a change in any numerical variable on the response.

Two class meetings from now, we’ll see how we can use the {marginaleffects} package to make our interpretations easier, especially for those of you without a calculus background.

Interpreting your Model

\(\bigstar\) Let’s try it! \(\bigstar\)

If you have a model that predicts prices of Air BnB rentals…

- provide interpretations of the intercept (if relevant) and the association between each surviving predictor and the response

Summary

We can use higher order terms to model associations that are more complex than “straight line”

Higher order terms include polynomial terms (a predictor to a positive integer power) and interaction terms (a product of two or more predictors)

We add polynomial terms to a model using the

{tidymodels}framework by appendingstep_poly()to our recipe- Models with polynomial terms approximate curved relationships between the predictor and response

- We use the

degreeargument ofstep_poly()to determine the degree of the polynomial term (higher degree means more wiggly, and more \(\beta\)-coefficients) - Setting

options = list(raw = TRUE)withinstep_poly()prevents the function from attempting to build “orthogonal polynomial terms” which would reduce interpretability

To interpret models with higher-order terms, we’ll need a bit of calculus (or help from a package like

{marginaleffects})- If a model \(\mathbb{E}\left[y\right] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \beta_2 x^2 + \cdots\) includes a second degree term for the predictor \(x\) and \(x\) is not included in any model terms other than those shown, the effect of a unit increase in \(x\) on the response \(y\) is an increase of about \(\beta_1 + 2\beta_2 x\)

Next Time…

Interaction Terms in Models (Mixed Effects)